November 15, 2016

Differentiating Gastrointestinal Pathogens from IBD and IBS

Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), as well as infections from GI pathogens can present very similar symptoms. A host of tests have been developed to aid in the differentiation between IBD and IBS, such as calprotectin and lactoferrin. However, there is still a need for more research to fully understand the process of differentiating gastrointestinal pathogens from IBD and IBS. In order understand these differences and uncover the true source of GI distress, researchers have been working to develop tools that can improve the process of identifying various GI protozoan parasites and bacteria linked to GI outbreaks around the world. These GI protozoans and parasites include Blastocystis, Entamoeba histolytica/dispar, Giardia lamblia, crytosporidium spp, and Clostridium difficile.

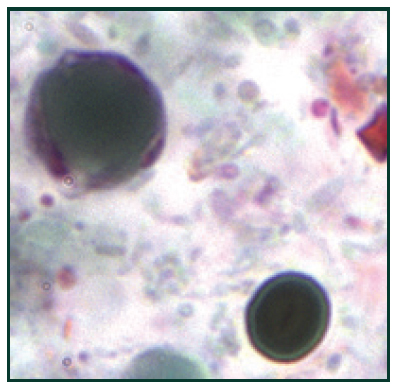

[caption id="attachment_3668" align="alignleft" width="200"] B. hominis cyst-like forms stained with trichrome14[/caption]

B. hominis cyst-like forms stained with trichrome14[/caption]

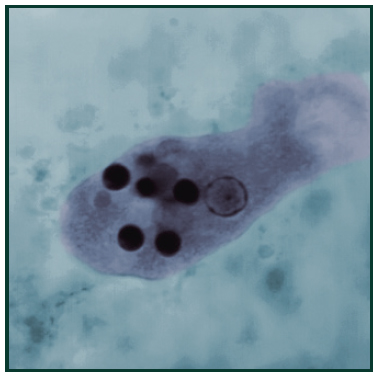

This trichrome-stained photomicrograph of an Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite, ingesting red blood cells which can be seen as dark inclusions15[/caption]

This trichrome-stained photomicrograph of an Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite, ingesting red blood cells which can be seen as dark inclusions15[/caption]

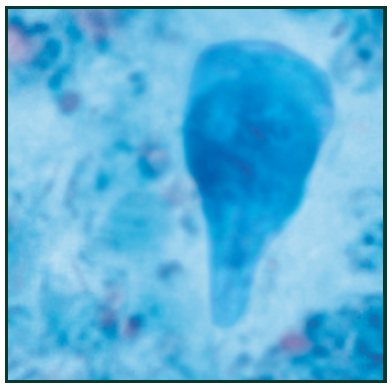

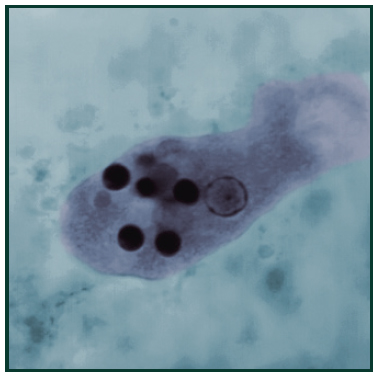

Trichrome stain of Giardia lamblia trophozoite16 [/caption]

Trichrome stain of Giardia lamblia trophozoite16 [/caption]

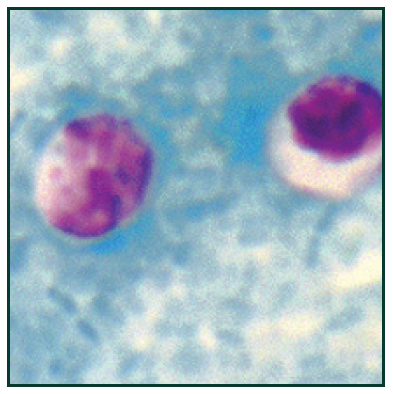

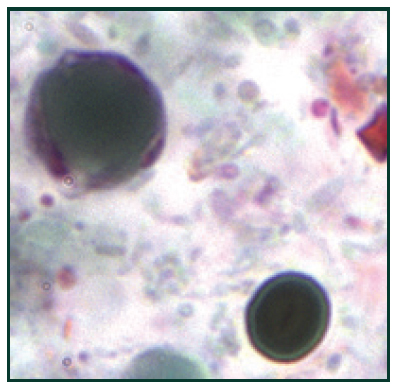

Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts stained with modified acid-fast17[/caption]

Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts stained with modified acid-fast17[/caption]

Stained photomicrograph of C. difficile18 [/caption]

Stained photomicrograph of C. difficile18 [/caption]

Although uncommon, the cytotoxin assay is considered gold standard method to identify infection. This functional test is based on the notion that C. difficile toxins have a cytopathic effect in cell culture that can be neutralized with specific anti-sera. However, the need for animal cell culture and the prolonged time to result vastly limit the use of this method, especially in small research labs.

Although uncommon, the cytotoxin assay is considered gold standard method to identify infection. This functional test is based on the notion that C. difficile toxins have a cytopathic effect in cell culture that can be neutralized with specific anti-sera. However, the need for animal cell culture and the prolonged time to result vastly limit the use of this method, especially in small research labs.

B. hominis cyst-like forms stained with trichrome14[/caption]

B. hominis cyst-like forms stained with trichrome14[/caption]

Blastocystis

Blastocystis is a prevalent enteric protozoan that infects a variety of vertebrates including humans, and also causes blastocystosis.1,2 Blastocystosis has been associated with abdominal pain, diarrhea, watery or loose stool, anal itching, weight loss and excess gas.3 In addition, it was recently suggested that a blastocystis infection could play a role in the etiology of IBS.4 Blastocystis is routinely detected by methods such as microscopy, culture and formyl acetate concentration technique (FECT). These methods, however, all have flaws making them unreliable and time-consuming. Since the protozoan has several morphological forms, microscopy is challenging. In addition, FECT is unreliable because it destroys the multivacuolar, vacuolar, and granular forms of the parasite during stool sample processing. Culture requires 2-3 days to diagnose and, in some instances, allows preferential growth of one subtype over another. Therefore, an ELISA-based test would offer superior accuracy along with a simpler and more convenient procedure for research labs. [caption id="attachment_3665" align="alignleft" width="200"] This trichrome-stained photomicrograph of an Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite, ingesting red blood cells which can be seen as dark inclusions15[/caption]

This trichrome-stained photomicrograph of an Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite, ingesting red blood cells which can be seen as dark inclusions15[/caption]

Entamoeba Histolytica/dispar

Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (E. histolytica/dispar) are intestinal protozoan parasites transferred via the fecal-oral route, and infect up to 10% of the human population.5 Entamoeba infections are most common in the developing world and are associated with poor sanitation where the entamoeba cysts are transmitted from contaminated food and water. Entamoeba histolytica contributes to amebiasis and is considered globally as a leading parasitic cause of human mortality. 5,6 The most common method of detection involves direct fecal smear (DFS) and staining which do not allow for the identification at the species level. Superior accuracy can be achieved through culturing fecal samples in Robinson’s or Jones’ mediums. New approaches to the identification of E. histolytica are based on detection of E. histolytica-specific DNA in stool and other samples. [caption id="attachment_3666" align="alignleft" width="200"] Trichrome stain of Giardia lamblia trophozoite16 [/caption]

Trichrome stain of Giardia lamblia trophozoite16 [/caption]

Giardia Lamblia

Giardia lamblia is a flagellated protozoan parasite that colonizes and reproduces in the small intestine, causing giardiasis.7 Giardia infection can occur through ingestion of dormant cysts in contaminated water, food, or by the fecal-oral route. In humans, infection is symptomatic only about 50% of the time. Symptoms of infection include diarrhea, malaise, excessive gas, steatorrhoea, epigastric pain, bloating, nausea, lack of appetite and weight loss.8 Giardia infection in humans is often incorrectly detected. Accurate detection requires an antigen test or, if unavailable, an ova and parasite examination of stool. Multiple stool examinations are recommended since the cysts and trophozoites are not shed consistently which can be costly and time consuming for researchers. [caption id="attachment_3664" align="alignleft" width="200"] Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts stained with modified acid-fast17[/caption]

Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts stained with modified acid-fast17[/caption]

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidiosis is caused by gastrointestinal infection with the protozoan parasite crytosporidium spp.9 Symptoms of cryptosporidiosis include watery diarrhea, stomach cramps, weight loss, nausea and fever. This highly pathogenic parasite is transmitted in contaminated water and by the fecal-oral route.10 Prevalence rates of crytosporidiosis in a symptomatic population in developed countries exceed 2-3%11. Serological surveys indicate that the vast U.S. majority has been exposed to this pathogen. In addition, this opportunistic pathogen is highly prevalent in immunocompromised people (e.g. 10-40% of those infected with HIV).11 The detection of crytosporidiosis is routinely performed by microscopic analysis of stool samples using organic dyes such as a Zeihl-Neelsen stain, fast acid stain or by immune-staining via direct fluorescent antibody (DFA). Since detecting cryptosporidium can be difficult, multiple stool samples may need to be collected over multiple days. DNA amplification techniques such as PCR or RT-PCR have also been reported, however, the equipment needed for those tests may not be readily available for every research lab. [caption id="attachment_3669" align="alignleft" width="200"] Stained photomicrograph of C. difficile18 [/caption]

Stained photomicrograph of C. difficile18 [/caption]

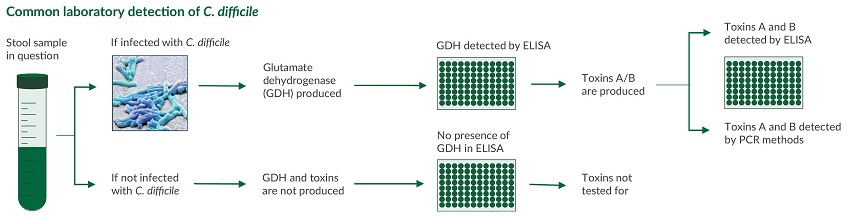

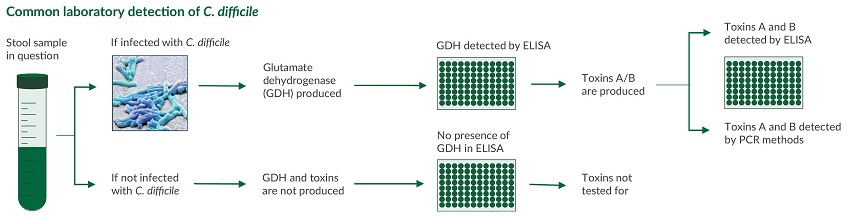

Clostridium Difficile GDH and A/B Toxin

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is an anaerobic, gram-positive bacterium causing symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon. C. difficile infection most commonly affects older adults in hospitals, and typically occurs after use of antibiotic medications as it competes with the normal, antibiotic sensitive gut flora. Early diagnosis and appropriate changes to antibiotic treatment regimens are vital to managing and controlling this infection.12,13 Laboratory detection of C. difficile infection is most commonly performed in a two-step algorithm: Although uncommon, the cytotoxin assay is considered gold standard method to identify infection. This functional test is based on the notion that C. difficile toxins have a cytopathic effect in cell culture that can be neutralized with specific anti-sera. However, the need for animal cell culture and the prolonged time to result vastly limit the use of this method, especially in small research labs.

Although uncommon, the cytotoxin assay is considered gold standard method to identify infection. This functional test is based on the notion that C. difficile toxins have a cytopathic effect in cell culture that can be neutralized with specific anti-sera. However, the need for animal cell culture and the prolonged time to result vastly limit the use of this method, especially in small research labs.

Improving the Process of Differentiating Gastrointestinal Pathogens from IBD and IBS

Protozoan parasites and bacteria such as Blastocystis, Entamoeba histolytica/dispar, Giardia lamblia, crytosporidium spp, and Clostridium difficile can wreak havoc on the GI system. Since the symptoms of having these gastrointestinal pathogen infections can manifest quickly or slowly, and show similar symptoms as IBD and IBS, it is important to understand the process of differentiating gastrointestinal pathogens from IBD and IBS. Older and time consuming techniques may not be accurate enough to differentiate between parasite, bacteria, and IBD/IBS. New technologies, such as GI pathogen assays, are helping researchers properly identify GI protozoan parasites and bacteria in order to uncover the correct sources of GI distress.References

- Stenzel et al. (1996). Blastocystis hominis revisited. Clin. Microbiol. Rev., 9(4), 563-84.

- Tan et al. (2004). Blastocystis in humans and animals: new insights using modern methodologies. Vet. Parasitol., 126(1-2), 121-44.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). CDC Fact Sheet. CDC.gov.

- Wawrzyniak et al. (2013). Bastocystis, an unrecognized parasite: An overview of pathogenesis and diagnosis. Ther. Adv. In Inf. Dis., 1(5), 167-178.

- WHO News and activities. (1997). Entamoeba taxonomy. World Health Organization, 75, 291–293.

- Diamond et al. (1993). A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudinn, 1903 (Emended Walker, 1911) separating it from Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925. k CG. A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudinn, 1903 (Emended Walker, 1911) separating it from Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 40(3), 340-4.

- Longo & Harrison. (2012). Online Chapter 199 Protozoal intestinal infections and trochomoniasis. Harrison's Internal Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Char et al. (1993). Impaired IgA response to Giardia heat shock antigen in children with persistent diarrhea and Giardiasis. Gut, 34(1), 38-40.

- Tzipori & Widmer. (2008). A hundred-year retrospective on cryptosporidiosis. Trends Parasitol., 24(4), 184-9.

- Chappell et al. (2002). Cryptosporidiosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis., 15(5), 523-7.

- Tzipori et al. (1995). Cryptosporidium and Cryptosporidiosis. Parasitology Today, 5, 4.

- Cloud et al. (2007). Update on Clostridium difficile associated disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol., 23(1), 4-9.

- Owens et al. (2008). Antimicrobial-associated risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis.,46 Suppl 1, S19-31.

- Centers for Disease Control. (2013). Global Health - Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. DPDx [Hominis image]. CDC.gov.

- Melvin & Greene. (1966). Center for Disease Control Public Health Image Library ID# 14544 [Entamoeba histolytica image]. phil.cdc.gov.

- Melvin. (1962). Centers for Disease Control Public Health Image Library ID# 338 [Giardia lamblia image]. phil.cdc.gov.

- Centers for Disease Control. (2013). Global Health - Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. DPDx [Cryptosporidium spp image]. CDC.gov.

- Hannel. (2016). [C. difficile image]. Savyon Diagnostics.