Diagnostic Testing in GI Health

60 to 70 million Americans are affected by gastrointestinal (GI) diseases and disorders each year. The estimated annual U.S. cost associated with GI disorders is over 140 billion dollars.1 Gl diseases and disorders can have a significant impact on quality of life, often contributing to anxiety and depression.2

Questions about GI biomarker tests?

Article: Diagnostic Testing in GI Health

The ongoing challenge relates to overlapping symptoms and the complex interconnection between the digestive system, immune system, nervous system, gut microbiota, and lifestyle factors. Identification of the underlying cause of stomach pain and associated GI symptoms is essential for timely treatment. Thankfully, GI diseases and disorders are gaining more focus in the medical community. Functional disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome and non-celiac gluten sensitivity, are now recognized as medical conditions. Tests for the identification of underlying causes of GI diseases and disorders are continuing to expand.

Infectious Diseases

A wide range of infectious diseases involve the GI tract. Food poisoning and traveler’s diarrhea are two common classes of infection that frequently affect individuals around the world. These viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections typically stem from contaminated food or water and can involve unsanitary handling of food products during any stage of food collection, transport, and preparation.3,4

Traveler’s Diarrhea

Traveler’s diarrhea affects as many as one million tourists each year. Approximately 60% of cases are caused by bacterial pathogens. Escherichia coli infections, primarily Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), account for most cases from Latin America, followed by norovirus infections. Campylobacter shigella and Salmonella infection are prevalent in South and Southeast Asia. Protozoa, including Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Entamoeba histolytica, typically account for about three percent of cases from Latin America and Africa and are often associated with prolonged infection. Five to ten percent of individuals who experience traveler’s diarrhea will develop irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, a chronic intestinal disorder. This is sometimes called post-infection IBS (PI-IBS).3

Food Poisoning

More than 48 million people experience food poisoning each year. Raw or undercooked meats, pork or poultry are associated with several potential pathogens, including Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Clostridium perfringens. Listeria is often linked to soft cheeses or deli meats, while Campylobacter is often associated with contaminated vegetables, milk, or water. E. coli, norovirus, and Staphylococcus aureus outbreaks are often traced to transfer from workers during food handling and preparation.4

Testing for Infectious Disease

Accurate diagnosis of a parasitic infection is required for proper treatment. Certain bacterial infections respond better to one antibiotic vs. another. Treatment of a viral infection with antibiotics will not fight the infection and may disrupt the normal balance of bacteria in the intestine, causing a state of dysbiosis.5 Stool-based tests for the detection of DNA or RNA from bacteria, viruses, or protozoa are frequently used to characterize an infection. Multiplex tests for up to four or five pathogens can not only help identify the type of pathogen but can often be used to differentiate between specific groups or strains to further assist with treatment selection.

Gastrointestinal Cancers and Screening

Cancers involving the digestive system affect more than 330,000 Americans each year and account for more than 160,000 deaths. Some cancers, including pancreatic cancer and liver cancer, currently lack an approved screening test for early detection and are associated with a high rate of mortality.6 For gastric and colorectal cancers, non-invasive screening is an effective tool, enabling prevention and early intervention.

Gastric Cancer

According to the American Cancer Society, Gastric Cancer affects more than 27,000 individuals each year and is responsible for more than 11,000 deaths.6 Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is the primary risk factor in the development of gastric (stomach) cancer. H. pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that infects the lining of the stomach. More than half of the world’s population is believed to be infected with H. pylori, with a higher incidence in developing countries. While most infected individuals show no symptoms, approximately two to three percent will eventually develop gastric cancer.7,8 H. Pylori is present in more than 75% of patients with MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma and up to 50% of gastric ulcers. Stool-based antigen tests are highly sensitive and specific for H. pylori infection. They are used to both detect infection and to confirm eradication of infection following treatment with antibiotics.9

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is cancer that occurs in the colon or rectum. Aging, IBD, and a family history of CRC are common risk factors.10 According to the American Cancer Society, colorectal cancer affects almost 150,000 Americans each year and is responsible for more than 50,000 deaths.6 As with most forms of cancer, early detection is critical for successful treatment and increased screening could save thousands of lives each year.

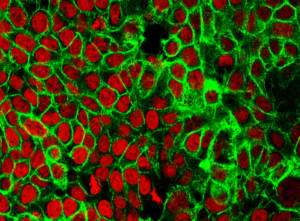

Colorectal Cancer Cells. Image credit NCI Center for Cancer Research

Fecal occult blood refers to blood in stool that is not visible to the naked eye but can be detected through immunochemical or chemical testing. Immunochemical fecal occult blood tests (iFOB), also called fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), use antibodies to detect hemoglobin in red blood cells that is indicative of blood in the stool. These non-invasive tests are widely accepted for the identification of patients suspected of having CRC requiring colonoscopy. Screening increases both the detection of benign (pre-malignant) polyps that can be removed before developing into colorectal cancer and the identification of asymptomatic, early-stage colorectal cancer that is easier to treat and has a lower mortality rate than later-stage cancer.10,11

Inflammatory Gastrointestinal Diseases and Biomarker Testing

While inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases can have symptoms that are identical to functional gastrointestinal disorders, inflammatory diseases involve damage to the intestine that can be confirmed via colonoscopy or endoscopy. Non-invasive screening tests for inflammatory biomarkers and target-specific antibodies are becoming indispensable tools in identifying suspected cases of inflammatory disease and prioritizing patients for colonoscopy.12

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

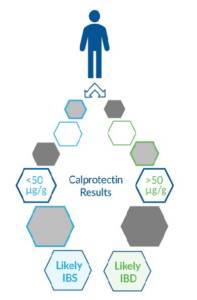

Inflammatory Bowel Disease, or IBD, is an inflammatory disease which causes chronic swelling and damage within the digestive tract. It encompasses both Crohn’s Disease, which can involve any part of the small or large intestine, and ulcerative colitis, which often affects the innermost lining of the large intestine (colon) and rectum. Symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and weight loss, are common to both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Heredity and/or a malfunctioning immune system are believed to play a role in disease etiology. Though IBD is not currently curable, treatment can include steroids, anti-inflammatory drugs, biologics (adalimumab, infliximab, etc.), and immune modifying agents.13,14 Neutrophils are immune cells that are recruited to sites of infection and assist in the digestion and clearance of pathogens. Calprotectin, along with granule proteins including lactoferrin, are released by neutrophils during inflammation. Elevated levels of calprotectin or lactoferrin in feces indicates the increased presence of neutrophils and inflammation in the intestines. Calprotectin and lactoferrin are proven biomarker tests that aid in the detection of IBD and the differentiation of IBD from Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). They have also been referenced in studies involving treatment monitoring.15,16

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is a hereditary autoimmune disease in which the body attacks the small intestine in response to the ingestion of gluten. These attacks lead to damage of the villi, the small fingerlike projections that line the small intestine, preventing proper nutrient absorption. Symptoms, if present, can include diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, bloating, vitamin deficiency, bone disease, and even skin disorders. While one percent of the worldwide population has celiac disease, it often goes undiagnosed. Treatment for celiac disease requires a gluten-free diet. Patients are often highly sensitive to very small amounts of gluten, even crumbs. Measurement of antibodies against deaminated gliadin peptide and tissue transglutaminase are often used in the diagnosis of celiac disease and the monitoring of adherence to a gluten-free diet.17,18

Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergies

Non-IgE-mediated food allergies involve a cell-mediated response to certain food proteins and often involve the activation and degranulation of eosinophils. A growing number of non-IgE-mediated food allergies and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) have been characterized based on clinical manifestations. Several non-IgE food allergies affecting infants and young children include food protein-induced proctocolitis (FPIAP), believed to be the most common non-IgE food allergy, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), and food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE).

All three often involve an allergy to cow’s milk, soy, or egg, but additional foods can be triggers for individual disorders and sometimes vary by geography. Increased levels of eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN) have been reported in stool samples from patients with FPIAP, FPIES, and FPE. A combination of fecal calprotectin and EDN testing has been used to differentiate FPIAP from functional (non-inflammatory) GI disorders.19,20 The immune system is incredibly complex and not yet fully understood. How does the immune system come to attack benign and even beneficial targets? How can this be prevented? How can we correct or specifically block a misdirected immune response? These are questions researchers are working to answer. For now, exclusion diets play a large role in the diagnosis and management of GI diseases and disorders involving food allergy or intolerance.

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

Functional GI disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and functional dyspepsia, affect more than 40% of people worldwide. They are often associated with chronic symptoms including pain, indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, and bloating. While functional disorders do not typically display the intestinal damage visible in inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases, there is increasing evidence that some subsets of functional disorders may, in fact, involve a low-level inflammatory response.2,21

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder involving the large intestine. Symptoms of IBS can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and weight loss. While the etiology of IBS in specific cases is typically unclear, potential causes are believed to include abnormal muscle contraction, nerve/signaling abnormalities, or an alteration in the gut microbiome. Recommended treatment can include lifestyle and/or diet changes, probiotics, and counseling. In some cases, food allergies and stress have been shown to aggravate IBS symptoms.22 Multiple studies have shown fecal calprotectin can be used to screen patients with GI symptoms and effectively differentiate between IBD and IBS, avoiding the need for colonoscopy in cases of IBS.22,12

Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Gluten sensitivity or gluten intolerance has been coined to describe individuals who experience symptoms consistent with celiac disease in response to gluten but lack the antibodies and intestinal damage observed in celiac disease. Symptoms can include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, nausea, and headache. Like celiac disease, treatment for non-celiac gluten sensitivity requires a strict gluten-free diet, as patients are often highly sensitive to very small amounts of gluten.23 Measuring antibodies against native gliadin may be useful in the diagnosis of NCGS and the monitoring of adherence to the gluten-free diet.

Intolerance Testing for Functional GI Disorders

Non-IgE-mediated food allergies or intolerances have been implicated in several inflammatory and non-inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders. While some researchers have hinted at the utility of IgG testing in the detection of food intolerance, IgG testing is an area of great controversy. This may stem from the misguided use of IgG test results in lieu of testing for IgE allergen sensitization, when, in fact, IgE-mediated allergic response is completely independent of an IgG-mediated immune response.24 This author recently experienced a bout of traveler’s diarrhea following a dive trip to Cozumel. Several weeks later, the symptoms seemed to re-appear. Was the infection recurring? Was I one of the five to ten percent of people who develop PI-IBS? I noted after a few rounds of illness that the timing seemed to coincide with consumption of cashews, though I’ve eaten them in the past without incident. Six weeks later, I had the opportunity to participate in a study involving multiplex IgE testing and multiplex IgG testing for the detection of allergen sensitization and food intolerance. My IgG test revealed a high level of IgG antibodies to cashews. This confirmed my suspicion. Research has shown, however, that a high level of IgG antibodies does not always indicate intolerance.24 My level of IgG antibodies to almonds was equally high, but I continue to eat those without incident. In this case, a general awareness of GI diseases and disorders combined with a focus on diet and the utilization of new testing options allowed for the identification of an underlying cause and targeted avoidance strategy.

Advancing Treatment and Outcomes

A wide range of gastrointestinal diseases and disorders have overlapping symptoms. Molecular testing, protein biomarker testing (including multiplex biomarker testing), and antibody screening, directed by recent experiences, heredity, diet and other lifestyle factors, can assist with diagnosis and the establishment of an effective treatment plan. In some cases, such as infection or early-stage cancer, the underlying cause can be cured. In other cases, such as a milk or soy allergy or an intolerance to gluten or cashews, comprehensive testing and careful analysis can lead to a highly targeted and effective avoidance strategy. For some patients, pharmaceuticals can be used to reduce inflammation and intestinal damage, reduce symptoms, and improve quality of life. Clinical research in the field of gastroenterology continues to uncover underlying causes of gastrointestinal disease and expand diagnostic tests and treatments, providing hope to millions of GI patients worldwide. Download a copy of the article »

References

- L. Digestive Diseases Statistics for the United States. NIDDK. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/digestive-diseases. Accessed March 31, 2022.

- J. Fikree, Asma and Peter Byrne. (2021). Management of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clinical Medicine. 21(1):44-52.

- D. de la Cabada Bauche, Javier and Herbert L. DuPont. (2011). New developments in traveler’s diarrhea. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 7(2): 88-95.

- E. Food Poisoning. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21167-food-poisoning. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- M. Connor, Bradley A., Traveler’s Diarrhea, CDC, https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea, Accessed March 28, 2022.

- I. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2022/2022-cancer-facts-and-figures.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- F. Diaz, P., et al. (2017). Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: adaptive cellular mechanisms involved in disease progression. 9(5).

- H. Wroblewski, L.E., et al. (2010). Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23(4): 713–739.

- G. Diacanu, S., et al. (2017). Helicobacter pylori infection: old and new. Journal of Medicine and Life. 10(2):112-117.

- K. Colorectal Cancer Screening Tests, American Cancer Society, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/screening-tests-used.html, accessed 14Apr2020.

- K2. Doubeni, C., 2020, Screening for colorectal cancer: Strategies in patients at average risk, UpToDate, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-colorectal-cancer-strategies-in-patients-at-average-risk/print, Accessed 14Apr2020.

- X. Banerjee, A, et al. (2015). Faecal calprotectin for differentiating between irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: a useful screen in daily gastroenterology practice. Frontline Gastroenterology. 6:20–26. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2013-100429.

- S. Ulcerative colitis. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ulcerative-colitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353326. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- T. Crohn’s Disease. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/crohns-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20353304. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- V. Bjarnason, I., 2017, The use of fecal calprotectin in inflammatory bowel disease, Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 13(1), 53-56.

- W. Buderas, S., at al. (2015). Fecal Lactoferrin: Reliable biomarker for intestinal inflammation in pediatric IBD. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. Volume 2015, Article ID 578527

- Q. Rubio-Tapia A, et al. (2013). ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol2013;108:656–676. PMID: 23609613.

- R. What is celiac disease? https://celiac.org/about-celiac-disease/what-is-celiac-disease/. Celiac disease foundation. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- N. Wada, T. et al. (2016). Increased CD69 expression on peripheral eosinophils from patients with food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 170:201–205

- O. Calvani, M. et al. (2021). Non–IgE- or Mixed IgE/Non–IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies in the First Years of Life: Old and New Tools for Diagnosis. Nutrients. 13, 226.

- Z. Choi, You Jin and Su Jin Jeong. (2019). Is fecal calprotectin always normal in children with irritable bowel syndrome? Intestinal Research. 17(4): 546-553.

- U. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. May Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20360016. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- P. Beyond Celiac. What is Non-celiac Gluten Sensitivity? https://www.beyondceliac.org/celiac-disease/non-celiac-gluten-sensitivity/what-is-it/ Accessed March 29, 2022.

- Y. Kanagaratham, C., et al. (2020). IgE and IgG antibodies as regulators of mast cell and basophil functions in food allergy. Frontiers in Immunology. 11:603050.